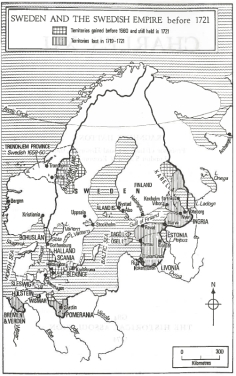

Sweden has had her share of memorable monarchs. In the 16th and 17th centuries, it seemed that every other ruler crowned in Stockholm was astonishing in one way or another. Gustav Vasa, Gustavus Adolphus, Queen Christina, Charles XI–between them, to the surprise of generations of students who have presumed that the conjunction of the words “Swedish” and “imperialism” in their textbooks is some sort of typographical error, they turned the country into the greatest power in northern Europe. “I had no inkling,” the writer Gary Dean Peterson admits in his study of this period, “that the boots of Swedish soldiers once trod the streets of Moscow, that Swedish generals had conquered Prague and stood at the gates of Vienna. Only vaguely did I understand that a Swedish king had defeated the Holy Roman Emperor and held court on the Rhine, that a Swede had mounted the throne of Poland, then held at bay the Russian and Turk.” But they did and he had.

The Swedish monarchs of this period were fortunate. They ruled at a time when England, France and Germany were torn apart by wars between Catholics and Protestants, as the great Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth began its steep decline and before Muscovy had transformed itself into Russia and begun its drive to the west. Yet their empire endured into the 1720s, and even then it took two decades of constant war to destroy it—not to mention an overwhelming alliance of all of their enemies, led by the formidable Peter the Great.

Much of the credit for Sweden’s protracted resistance rests with the fifth, last and most controversial of this line of notable rulers: Charles XII (1682-1718). An endlessly fascinating figure—austere and fanatical, intelligent yet foolhardy—Charles has some claim to be the greatest of Swedish kings. Voltaire, an admirer, dubbed him “the Lion of the North,” and though he was at heart a soldier, whose genius and speed of movement earned him the nickname “the Swedish Meteor,” he was also a considerable mathematician with a keen interest in science. In other circumstances, Charles might have turned himself into an early example of that 18th-century archetype, the enlightened despot. Yet plenty of Swedes, then and now, despised their king for impoverishing the country and sacrificing thousands of his subjects by fighting almost from the moment he ascended the throne in 1697 until he died two decades later. For the playwright August Strindberg, he was “Sweden’s ruin, the great offender, a ruffian, the rowdies’ idol.” Even today, the king’s biographer Ragnhild Hatton observed, “Swedes can be heard to say that no one shall rob them of their birthright to quarrel about Charles XII.”

Charles came to the throne at a critical moment. The Swedes had spent a century making enemies, all of whom now combined against them, hoping to take advantage of the new king’s youth and inexperience. Charles fought them doggedly, confronting overwhelming odds, and swiftly proved himself to be among the greatest generals of the age. But he also made grievous mistakes, and missed more than one opportunity to bring hostilities to an end when he could have obtained decent terms. By fighting on, he condemned Sweden’s empire to dismemberment.

None of this was obvious at first. The early years of the Great Northern War of 1700-21 were a period of Swedish triumph; confronting a formidable alliance of Russia, Poland, Saxony and Denmark, the teenaged Charles drove the Danes out of the war in a few weeks before turning on Peter the Great and his Russians. At the Battle of Narva (November 1700), fought in a blizzard in Estonia, the king, then still 18, led an army that was outnumbered four to one to the most complete victory in Swedish history. The Saxons and the Poles were defeated next, and the Polish king replaced by a Swedish puppet. This would, no doubt, have been the moment to make peace, but Charles refused to consider ending what he considered to be an “unjust war” without securing outright victory. He chose to invade Russia.

So many of the Meteor’s decisions had been right thus far, but this one was rash and catastrophic. There were a few early successes—at Holovzin, in 1708, Charles routed the Russians (who outnumbered him on this occasion three to one) by completing a forced march through a marsh in pitch dark and driving rain. Swedish casualties were unsustainable, however, and a few months later, at Poltava, what remained of Charles’s army confronted a large, well-trained and modernized Russian force, the product of Tsar Peter’s energetic military reforms.

The king was not available to lead his men. A week earlier, Charles had been struck in the foot by a musket ball—his first injury in a decade’s fighting—and by the time battle commenced he was weakened by blood poisoning and wracked with fever. At the same time, it might be argued that the position was already hopeless. Sweden was a nation of 2.5 million confronting one that was four times her size; worse, Charles had led his men into the heart of Russia, stretching his supply lines to the breaking point. When his Swedes were routed, and 7,000 of them killed, the king had no choice but to flee to sanctuary in the Ottoman Empire, where he would remain in semi-captivity for four years.

Looking back across the centuries, Poltava assumes additional significance. It was always clear it was a decisive battle–one that ensured Russia would win the war. What was less obvious was that the peace that eventually followed would change the face of Europe. Under the terms of the Treaty of Nystad (1721), Peter the Great occupied Sweden’s Baltic provinces and wasted little time in building a new capital, St. Petersburg, on the site of the old Swedish fortress of Nyenskans. With that, Russia’s entire focus shifted; a nation that had spent centuries looking east and confronting the Tatar threat now had a window on the West, through which new ideas would flow and new rivalries come into focus.

Very little went right for Charles XII after Poltava. Sweden lost Bremen and Pomerania, its imperial possessions in Germany, and a hostile ruler seized the throne of Poland. Even the Meteor’s return home in the autumn of 1714—accomplished, in typical fashion, by a pell-mell ride across half of Europe that he completed in just 15 days—did little to redress the shifting balance of power. The only enemy that Charles could then confront on equal terms was Denmark, and it was in Danish-held Norway that the king fell in battle in December 1718. He was just 36 years old.

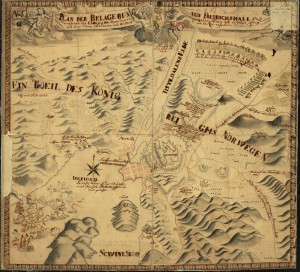

Even in death, Charles remained extraordinary, for the circumstances in which he died were very strange. The king was shot through the head while conducting a siege at Fredrikshald, a hilltop fortress just across the Danish border—but there have been many who have tried to prove that the bullet or shell fragment that killed him had not been fired from within the fortress. The Meteor, it has been repeatedly argued, was murdered by one of his own men.

Saying with any certainty what happened to Charles XII is difficult; for one thing, while plenty of people were around him when he died, not one witnessed the instant of his death. The king had gone forward one evening after dark to supervise the construction of a front-line trench well within range of Danish musket fire. It was a deadly spot—nearly 60 Swedish trench diggers had already been killed there—and though he waited until well after dark to visit, there were flares burning on the fortress walls, and “light bombs,” an 18th-century version of star shells, illuminated the scene. Charles had just stood to survey the construction, exposing his head and shoulders above the breastworks, when he slumped forward. A large-caliber projectile had entered his head just below one temple, traveled horizontally through his brain, and exited through the far side of his skull, killing him instantly.

The first instinct of the men standing below Charles in the trench was not to investigate what had happened, but to get the king’s body out of the trenches without demoralizing the rest of the army. Later on, though, several government commissions took evidence from the men who had been in the trench that night. Most thought that the shot had come from the left–the direction of the fortress. But none had seen it strike the king.

Expert testimony makes it clear that there was nothing inherently suspicious about Charles’s death. He had been within easy reach of Danish guns, and might easily have been hit by grapeshot from a big gun or a sniper’s bullet. Yet there is at least a prima facie case for considering other possibilities. It has been claimed, for instance, that the guns of Fredrikshald were not firing at the time the king was hit (untrue) and that there were plenty of people on the Swedish side who might have wished Charles dead (a lot more likely). From the latter perspective, the suspects included everybody from an ordinary Swedish soldier tired of the Meteor’s never-ending war to the principal beneficiary of Charles’s death: his brother-in-law, who took the throne as King Frederick I, immediately abandoned the attack on Norway and soon ended the Northern War. It is possible to argue, too, that every wealthy Swede profited from the Meteor’s demise, since one of Frederick’s first acts was to abandon a widely hated 17 percent tax on capital that Charles’s efficient but despised chief minister, Baron Goertz, was on the point of introducing. Goertz was so loathed by 1718 that it has been suggested that the real motive for killing Charles might have been to get to him. It is true that the baron was arraigned, tried and executed within three months of his master’s death.

The written evidence does suggest that some of those in the king’s circle behaved oddly both before and after he was shot. According to an aide-de-camp, albeit writing 35 years later, Prince Frederick seemed extremely nervous on the last day of Charles’s life and regained his composure only after being told the king was dead. And Frederick’s secretary, André Sicre, actually confessed to Charles’s murder. The value of Sicre’s “statement” remains disputed; he had fallen ill with fever, made his admission in the throes of a delirium and hastily recanted it when he recovered. But there is also an odd account that Melchior Neumann, the king’s surgeon, scribbled inside the cover of a book. The Finnish writer Carl Nordling recounts that, on April 14, 1720, Neumann

dreamed he saw the dead king on the embalming table. Then the king regained life, took Neumann’s left hand and said, “You shall be the witness to how I was shot.” Agonized, Neumann asked: “Your Majesty, graciously tell me, was Your Majesty shot from the fortress?” And the king answered: “No, Neumann, es kam einer gekrochen”—”One came creeping.”

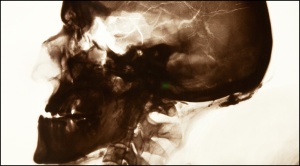

The forensic evidence–which, perhaps surprisingly for a death that took place nearly 300 years ago, survives in abundance—offers rather surer ground. Charles’s thick felt hat, for instance, remains on display in a Swedish museum, bearing a hole 19 millimeters in diameter, or about three quarters of an inch—a clear indicator of the size, and hence perhaps the type, of the projectile that killed him. The king’s embalmed and mummified body lies in a Stockholm church, from which it has been exhumed three times–in 1746, 1859 and 1917– and on the last of these occasions X-rays were taken of the corpse and a full autopsy performed in the hope of resolving the vexed question of whether he was murdered. As we will see, even the projectile that is supposed to have killed Charles has survived.

The real question, of course, is, from which direction was he hit? Those who have studied the case generally agree that, given the orientation of the trench in which the king was standing, an object striking him on the left side of the head must have come from the fortress, whereas a shot fired from the right would most likely have originated from the Swedes’ own trench system. Examination of Charles’s body suggests that he was, in fact, shot from the right–what appears to be the entry wound on that side of his skull is significantly smaller than the apparent exit wound on the left.

Yet this and virtually every other forensic detail has been contested. Examination of Charles’s hat, on display in a Stockholm museum, reveals a single prominent hole on the left side. Does this mean that he was actually shot from Fredrikshald–or merely that he wore his headgear at a rakish tilt? Similarly, trials have shown that, in some circumstances, entrance wounds can be larger than exit holes, and while the exhumation of 1859 found that Charles XII had been killed by the enemy, those of 1746 and 1917 argued that he had been murdered. Historians have established that Danish shells dating to the correct period contained iron shot of the correct dimensions, but they have also demonstrated that the guns capable of firing them remained silent that night while only the largest howitzers fired. Nordling, meanwhile, argues that the absence of lead splinters in the dead king’s skull suggests that he was assassinated with an exotic piece of ammunition: a silver bullet or a jacketed round of some description. Either option seems extravagant, not least because jacketed ammunition dates only to the 19th century–but even this sort of speculation pales in comparison with the suggestion that Charles was felled not by a bullet but a button.

Every historian considering the “bullet-button” (kulknappen) hypothesis is indebted to the folklorist Barbro Klein, who set out a mass of data in a paper published in 1971. Klein showed that an eighteenth century assassin might well have feared that the king could not be felled by ordinary ammunition; a considerable body of contemporary legend attests to the fact that Charles was considered “hard” during his lifetime (that is, invulnerable to bullets). And a fragment collected by the folklorists Kvideland and Sehmsdorf suggests that some people, at least, believed the king was literally bulletproof, and that rounds aimed at him would strike a sort of spiritual force-field and fall straight to the ground:

No bullet could hit Charles XII. He would free his soldiers for twenty-four hours at a time, and no bullet could hit them during that time period either…. He would take his boots off whenever they were full of bullets, saying that it was hard to walk with all these “blueberries” in his boots.

The strangest piece of evidence in this strange tale is a “curious object” brought into the museum at Varberg in May 1932 by Carl Andersson, a master smith. Andersson handed over “two half-spheres of brass filled with lead and soldered together into a ball, with a protruding loop that testified to its former use as a button.” One side was flattened, “the result of a forceful collision with a hard surface.” He had found the button, he said, in 1924 in a load of gravel he had hauled from a pit near his home.

According to Klein, the kulknappen fits neatly with another Swedish tradition–one suggesting that Charles’s magical protection had been breached by a killer who used the king’s own coat button to kill him. More than that: versions of this same bit of folklore tie the object to the gravel pit where it was found. These stories say a Swedish soldier “found the bullet… and brought it with him home.” They end with the man bragging about his find, only to be warned by the local priest that the killers might come after him. He solves the conundrum by hurling the evidence into the very quarry from which Andersson’s bullet-button was eventually recovered.

On close examination, there is reason to doubt the accuracy of this tradition; few of the tales that Klein collected date to before 1924, and Professor Nils Ahnlund has published a scathing commentary on the dangers of using such folklore as historical evidence. But there are at least three details that give one pause for thought. One is another legend that names the soldier who found the bullet as “Nordstierna”–which, as Klein notes, really was the name of a veteran of the Northern War who farmed at Deragård, the spot where the bullet-button was recovered. The second is the diameter of Andersson’s find: 19.6 millimeters (0.77 inches), a very close match to the hole in Charles’s hat.

What, though, of the third detail? For this, we need to turn to a much more recent piece of evidence: an analysis by Marie Allen, of Uppsala University,who in 2001 recovered two traces of DNA from the kulknappen. One of those fragments, lodged deep within the crevice where the two halves of the button were soldered together, came from someone with a DNA sequence possessed by only 1 percent of the Swedish population. And a sample taken from the bloodstained gloves that Charles XII wore on his last night revealed an identical sequence; the king, it seems, belonged to that same tiny group of Swedes.

As things stand, then, little has been resolved. The historian naturally revolts against the outlandish notion that Charles XII was killed by an assassin who believed he was invulnerable to bullets, who was somehow able to obtain a button from the king’s own coat—and possessed such skill as a marksman that he could hit his target in the head from 20 or 30 yards, using an irregularly shaped projectile, in the middle of a battle and in almost total darkness.

Yet if advances in DNA analysis prove anything, it is that there is always hope in cold cases. Allen’s evidence may be inconclusive, but it is at least intriguing. And there is always the chance that further developments in technology may prove a closer match. Sweden lost a king when the Meteor fell to earth. But she certainly gained a mystery.

Sources

Anon. “A royal autopsy delayed 200 years.” In New York Times, September 16, 1917; Jan von Flocken. “Mord oder heldentod? Karl XII von Schweden.” Die Welt, August 2, 2008; Robert Frost. The Northern Wars: War, State and Society in Northeastern Europe, 1558-1721. London: Longman, 2001; R.M. Hatton. Charles XII of Sweden. New York: Weybright and Talley, 1968; Ragnhild Hatton. Charles XII. London: Historical Association, 1974; Barbara Kirschenblatt-Gimblett. “Performing knowledge.” In Pertti Anttonen et al (eds.), Folklore, Heritage, Politics, and Ethnic Diversity: Festschrift for Barbro Klein. Botkyrka: Mankulturellt Centrum, 2000; Barbro Klein. “The testimony of the button.” Journal of the Folklore Institute 8 (1971); Reimund Kvideland and Henning Sehmsdorf (eds). Scandinavian Folk Belief and Legend. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1988; Gary Dean Peterson. Warrior Kings of Sweden: The Rise of an Empire in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries. Jefferson., NC: McFarland, 2007; Carl O. Nordling. “The death of King Charles XII–the forensic verdict.” Forensic Science International 96:2, September 1998; Stewart Oakley. War and Peace in the Baltic 1560-1719. Abingdon, Oxon.: Routledge, 1974; Michael Roberts. The Swedish Imperial Experience 1560-1718. Cambridge: CUP, 1984.