It was a typhoon, or so it’s said, that cast up David O’Keefe on Yap in 1871, and when he finally left the island 30 years later, it was another typhoon that drowned him as he made his way home to Savannah.

Between those dates, though, O’Keefe carved himself a permanent place in the history of the Pacific. So far as the press was concerned, he did it by turning himself into the “king of the cannibal islands”: a 6-foot-2, red-haired Irishman who lived an idyllic tropical existence, was “ruler of thousands” of indigenous people, and commanded “a standing army of twelve naked savages.” (“They were untutored, but they revered him, and his law was theirs.”) [New York Times; New York Tribune; Watchman & Southron] It was this version of O’Keefe’s story that made it to the silver screen half a century later in the forgettable Burt Lancaster vehicle His Majesty O’Keefe (1954), and this version, says scholar Janet Butler, that is still believed by O’Keefe’s descendants in Georgia. [Butler pp.177-8, 191]

The reality is rather different, and in some ways even more remarkable. For if O’Keefe was never a king, he certainly did build the most successful private trading company in the Pacific, and—at a time when most Western merchants in the region exploited the islanders they dealt with, then called in U.S. or European warships to back them up—he worked closely with them, understood them and made his fortune by winning their trust and help. This itself makes O’Keefe worthy of remembrance, for while the old sea-captain was most assuredly not perfect (he had at least three wives and several mistresses, and introduced the Yapese to both alcohol and firearms), he is still fondly recalled on the island. It doesn’t hurt, so far as the strangeness of the story goes, that O’Keefe ingratiated himself on Yap by securing a monopoly on the supply of the island’s unique currency: giant stone coins, each as much as 12 feet in diameter and weighing up to four and a half tons. But wait; we’re getting ahead of ourselves.

Let’s start with the convoluted history that brought O’Keefe to Yap.

So far as it is possible to tell, the captain was born in Ireland around 1823, and came to the U.S. as an unskilled laborer in the spring of 1848. [Butler pp.26-7] This date strongly suggests that he was one of more than a million emigrants driven from Ireland by the potato famine that began in 1845, but—unlike the many Irish who landed in New York and stayed there—O’Keefe continued traveling, eventually washing up in Savannah in 1854. After working on the railroads, he went to sea and worked his way up to be captain of his own ship. During the Civil War, it is said, he worked as a blockade runner for the Confederacy. [Butler pp.76-8; Hezel]

Whatever the truth, O’Keefe did flourish briefly in the Reconstruction period before the hot temper he was noted for landed him in serious trouble. As captain of the Anna Sims, moored in Darien, Georgia, he got into a violent argument with a member of his crew. The sailor hit O’Keefe with a metal bar; O’Keefe retaliated by shooting the man through the forehead. He spent eight months in jail charged with murder before winning an acquittal on the ground of self-defense, and at around the same time—it was now 1869—he married a Savannah teenager named Catherine Masters. [Butler pp.33-4, 79-80]

What drove O’Keefe from Georgia remains a minor mystery. Family tradition holds that he knocked a second crewman into the Savannah River some months later; fearing he had drowned the man, O’Keefe signed up to join the steamer Beldevere, fleeing to Liverpool, Hong Kong and the Pacific. [Butler p.80] Yet there seems to be no evidence that this fight actually occurred, and it’s just as likely that fading fortunes drove the Irishman to desperation. One historian points out that, by 1870, O’Keefe had been reduced to running day excursions up the coast for picnickers. [Hezel]

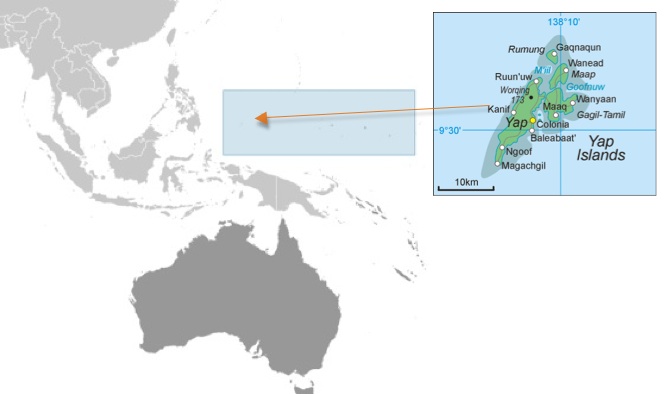

In any event, the captain left Savannah, and little seems to have been heard from him until he popped up in Hong Kong late in 1871, writing to send his wife a bank draft for $167 and vowing that he’d be home by Christmas—a promise that he failed to fulfill. The next Catherine O’Keefe heard from her husband was when he wrote requesting that she send him the Master’s certificate he needed to skipper a ship—a sure sign that he was staying put in the Pacific. By early 1872 O’Keefe was in Yap, a little archipelago of connected islets in the Carolines. [Hezel]

There were good reasons for liking Yap. The island lies just above the Equator in the western part of the Pacific and was well placed for trade, being within sailing distance of Guam, the Philippines, Hong Kong and the East Indies (Indonesia). The people there were welcoming at a time when those on other islands were still killing foreigners. And Yap was extremely fertile. Coconut trees abounded, which made the place attractive to dealers in copra (dried coconut flesh, an important source of lamp oil), while the lagoons teemed with sea cucumbers—bêche-de-mer, a noted Asian delicacy.

According to traditional accounts, O’Keefe came to Yap more or less by chance—washed ashore in a typhoon and found and nursed to health by a Yapese man named Fanaway, who taught him something of the local language. [Butler pp.38, 95, 167-8] That version of events is certainly what his family believed, but local tradition suggests that O’Keefe actually came to Yap to trade, arriving in a Hong Kong junk named Catherine in honor of his wife, and simply liked the place so much he stayed. [Hezel] Whichever story is correct, though, it did not take him long to shrug off family ties. Catherine O’Keefe was never actually abandoned—her husband continued to send her substantial sums once or twice a year, and the last draft drawn on his business in Yap was received in Savannah as late as 1936. [Butler p.143] O’Keefe’s letters home, though, quickly became less and less affectionate, the closings moving within months of his arrival from “Your loving husband” through “Good bye, yours truly” to a frankly discouraging “Yours as you deserve.” [Butler pp.85-6]

It is not difficult to understand why Catherine, miles away in the United States, soon faded in her husband’s memory. Life in the Pacific was less than idyllic at first; O’Keefe, who was employed for his first few years by the Celebes South Sea Trading Company, was sent on a dangerous mission to the Hermit Islands in search of bêche-de-mer, losing so many of his men to fever that he never again sailed to Melanesia. Soon after that, he lost his job when his boss was killed by an ax blow to the head on Palau, and he spent the remainder of the 1870s struggling to build up a business of his own. That meant establishing a network of trading stations in the face of competition, recruiting European agents of dubious reliability on the waterfronts of Hong Kong and Singapore, and slowly adding sailing vessels to his fleet: the Seabird in 1876, the Wrecker in 1877, the Queen in 1878 and the Lilla in 1880. [Hezel]

Two epiphanies turned O’Keefe from just another trader into the greatest merchant for thousands of miles around. The first came when he called at the Freewill Islands, off the north coast of New Guinea, sometime early in the 1870s and recognized the vast commercial potential of a narrow islet called Mapia, which was nine miles long and densely forested with coconut. Most of the native Mapians had been killed in raids launched by the ruler of nearby Ternate; the Irishman visited the sultan and concluded a treaty with him that gave O’Keefe exclusive rights to harvest coconuts on Mapia in return for $50 a year. By 1880, the little sandspit was producing 400,000 pounds of copra a year; the sultan kept his side of the bargain and turned away rival traders eager to claim to part of this bonanza. [Butler pp.65, 111; Hezel]

The second epiphany, which did not strike until a little later, came on Yap itself, and it secured O’Keefe the undying loyalty of the islanders. As the Irishman got to know Yap better, he realized that there was one commodity, and only one, that the local people coveted—the “stone money” for which the island was renowned and that was used in almost all high-value transactions on Yap. These coins were quarried from aragonite, a special sort of limestone that glistens in the light and was valuable because it was not found on the island. O’Keefe’s genius was to recognize that, by importing the stones for his new friends, he could exchange them for labor on Yap’s coconut plantations. The Yapese were not much interested in sweating for the trader’s trinkets that were common currency elsewhere in the Pacific (nor should they have been, a visitor conceded, when “all food, drink and clothing is readily available, so there is no barter and no debt” [Furness p.92]), but they would work like demons for stone money.

The coins, known as fei, were quarried 250 miles away on Palau, and they varied in size from a few inches to nearly 10 feet in diameter. Each was carefully carved and was thicker toward the center than around the edges; each had a hole bored through the middle, and the larger ones were transported on poles hauled around by gangs of islanders. The coins’ value was not dependent solely on their size, however; it was measured by a complex formula that included acknowledgement of their age, their quality and the number of lives that had been lost in bringing them to Yap. Nor did the larger coins (which were invariably the property of chiefs) literally change hands when they were used in a transaction; they were usually set up just outside a village, and stayed in their accustomed place. Every one of the 6,000 Yapese, the visiting anthropologist William Furness found in 1908, seemed to know who owned which coin, and some could trace that ownership back through centuries of trade.

It was not even necessary for a coin to reach Yap to be valuable; Furness told of one gigantic fei that had been lost when the canoe carrying it sank; enough survivors “testified to its dimensions and fineness” for its worth to be recognized, and it remained the valuable property of the chief who had sponsored its carving, even though it lay in several hundred feet of water miles from the coast. [Furness pp.94-7; Berg p.150]

The Yapese may have been using fei as early as 1400, though the stones were so difficult to quarry with shell tools and then transport that they remained very rare as late as 1840. [Price p.76; Berg pp.151-4; Gillilland p.3] Their existence was first detailed by one of O’Keefe’s predecessors, the German trader Alfred Tetens, who in 1865 traveled to Yap on a large ship ferrying “ten natives… who wished to return home with the big stones they had cut on Palau.” [Gillilland p.4] It’s clear from this that the Yapese were eager to find alternatives to transportation by canoe, and O’Keefe fulfilled this demand. By 1882, he had 400 Yapese quarrying fei on Palau—nearly 10 percent of the population. [Berg p.150]

This trade had its disadvantages, not least the introduction of inflation, caused by the sudden increase in the stock of money. But it made huge sense for O’Keefe. The Yapese, after all, supplied the necessary labor, both to quarry the stones and to harvest coconuts on Yap. O’Keefe’s expenses, in the days of sail, were minimal, just some supplies and the wages of his crewmen. In return, he reaped the benefits of thousands of man-hours of labor, building a trading company worth—estimates differ—anywhere from $500,000 to $9.5 million. [Evening Bulletin; Hezel]

Wealthy now, and no man’s servant, the Irishman felt free to indulge himself. He took two more wives—the first, who stayed on Mapia, was Charlotte Terry, the daughter of an island woman and the ex-convict employed to manage O’Keefe’s affairs there; the next, even more scandalously, was Charlotte’s aunt. This third wife, whose name was Dolibu, was a Pacific islander from Nauru. Widely believed to be a sorceress who had ensnared O’Keefe with magic, Dolibu set up home with him on Yap, had several children, and issued orders that her niece’s name should not be mentioned in her company. [Butler pp.39-41, 111; Hezel]

By the early 1880s, David O’Keefe was rich enough to build himself a red brick home on Tarang, an island in the middle of Yap’s harbor. Aside from a large library of all the most fashionable books—the captain enjoyed a reputation as an avid reader—he imported a piano, silver utensils and valuable antiques, and his property included four long warehouses, a dormitory for his employees, a wharf with moorings for four ships, and a store known as O’Keefe’s Canteen that sold the locals rum at 5 cents a measure. There were always plenty of people milling about: the canteen was run by a man named Johnny who was said to be a thief, a drunkard and a mechanical genius; Dolibu was waited on by two cooks and a houseboy; and there was also a Yapese loading crew paid “fifty cents a day plus some grub and drink.” And though Yap was, nominally, part of Spain’s overseas empire after 1885 (and German after 1898), O’Keefe flew his own flag over Tarang —the letters OK in black on a white background. [Hezel; Butler pp.60-1, 104, 108-09]

There are many tales of O’Keefe’s kindess to the Yapese, and it is perhaps too easy, looking back, to criticize the sale of rum and guns to the islanders; those who visited Yap were adamant that the Irishman sold alcohol only because rival traders—and the Spanish and German governments—did, too. There were limits to this benevolence, however, and O’Keefe certainly saw nothing wrong in exploiting the vast gap between Western prices and Yapese incomes. John Rabé, who went to Yap in 1890, recorded that O’Keefe swapped one piece of stone money four feet in diameter—which the Yapese themselves had made, but which he had imported on one of his ships—for 100 bags of copra that he later sold for $41.35 per bag. [Butler pp.103-04]

For the best part of 20 years, O’Keefe enjoyed the fruits of his and his men’s labor. Twenty or 30 sailing ships a year now called at Yap, which had become the greatest entrepôt in the Pacific, and a large steamer anchored every eight weeks to pick up copra and offload trade goods. All this, of course, earned the Irishman enmity, one visitor noting that O’Keefe was “at war with all the other whites of the Island, all of whom thoroughly detest him”; by 1883 feeling was running so high that numerous charges of cruelty were lodged when a British warship called at the island. These included allegations that Yap men serving on the Lilla had been hung by their thumbs and flogged, or thrown overboard in shark-infested waters. But when the captain of HMS Espiègle investigated, he found the charges “totally unfounded.” O’Keefe, he ruled, had been maliciously wronged by rivals “jealous at the success of his relations with the natives.” [Hezel]

It was not until around 1898 that O’Keefe’s fortunes waned. Leaf lice—pests brought to the island in trading cargoes–began to infest Yap’s plantations, cutting production of copra to as little as 100 tons a year; the island was hit by two massive typhoons, and the Germans were most displeased by the captain’s stubborn independence. At last, in April 1901, O’Keefe quit Yap. He left Charlotte and Dolibu behind, but took with him his two eldest sons, apparently intending to return at long last to Savannah.

He never made it. Sometime in May 1901, his ship, the schooner Santa Cruz, was caught in another typhoon and sunk far out in the Pacific. The Irishman was never seen again, although one odd story from Guam has it that some six months later a ship called there seeking permission to bury the body of a shipwrecked man. He had been picked up clinging to a spar and dying of starvation, and had given his name as O’Keefe. [Savannah Morning News]

News of the captain’s death took time to reach Georgia, but when it did it aroused a mixture of horror—at O’Keefe’s bigamous marriages to non-Caucasian women— and greed. Catherine, outraged to discover that her husband’s will assigned his fortune to Dolibu, hired a Savannah attorney to travel to Yap and lay claim to his property. Despite a promise to return from Yap with at least half a million dollars, the man eventually settled on Catherine’s behalf for a mere $10,000. But for years, until her own death, in 1928, she haunted the Savannah courthouse, “a tall gaunt woman… very erect… always dressed in funeral black,” and still hoping vainly to secure “what was rightfully hers.” [Butler p.33; Hezel]

With O’Keefe dead and the Germans thoroughly entrenched, things began to go badly for the Yapese after 1901. The new rulers conscripted the islanders to to dig a canal across the archipelago, and, when the Yapese proved unwilling, began commandeering their stone money, defacing the coins with black painted crosses and telling their subjects that they could only be redeemed through labor. [Labby p.3] Worst of all, the Germans introduced a law forbidding the Yapese from traveling more than 200 miles from their island. This put an immediate halt to the quarrying of fei [Butler p.113; Speedy], though the currency continued to be used even after the islands were seized by the Japanese, and then occupied by the United States in 1945.

Today, Yap forms part of the independent Federated States of Micronesia, and most day-to-day transactions on the island are carried out in dollars. David O’Keefe’s memory remains alive on the island, though, and not just in the form of places such as O’Keefe’s Kanteen, which cater to tourists. The island’s stone money is still exchanged when Yapese transfer rights or land. And while it remains in use, perhaps, a little of David O’Keefe still haunts the friendly island that he loved.

Sources

Most accounts of O’Keefe’s career are largely fictional, and there are only two reliable sources for his life and times: Butler’s doctoral thesis and Hezel’s Journal of Pacific History article. I have used both extensively.

Anon. ‘King O’Keefe of Yap.’ The Watchman and Southron (Sumter SC), December 11, 1901; ‘The cannibals made Captain O’Keefe a king.’ New York Times December 7, 1901; ‘An Irishman who became king’. New York Tribune, April 19, 1903; ‘Wants island of Yap.’ Evening Bulletin (Honolulu), May 18, 1903; ‘King of Yap buried.’ Savannah Morning News, June 1, 1904; ML Berg. ‘Yapese politics, Yapese money and the Sawel tribute network before World War I.’ Journal of Pacific History 27 (1992); Janet Butler. East Meets West: Desperately Seeking David Dean O’Keefe from Savannah to Yap. Unpublished Ed.D. thesis, Georgia Southern University, 2001; William Henry Furness III, Island of Stone Money: Uap of the Carolines. Philadelphia: JP Lipincott, 1910; Francis X. Hezel. ‘The man who was reputed to be king: David Dean O’Keefe.’ Journal of Pacific History 43 (2008); Cora Lee C. Gillilland, ‘The stone money of Yap’. Smithsonian Studies in History and Technology 23 (1975); David Labby, The Demystification of Yap: Dialectics of Culture on a Micronesian Island. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1976; Willard Price, Japan’s Islands of Mystery London: William Heinemann, 1944; Allan Speedy, ‘Myths about Yap stone money’ http://www.coinbooks.org/esylum_v13n51a15.html, accessed July 2, 2011.