For very nearly all its course, the Blavet is a placid river. It winds its way through central Brittany: broad, unhurried, gentle and unthreatening, a favourite among fishermen, and – for the century or so since it was dammed at Guerlédan, creating a substantial lake – a magnet for holidaymakers, too. Yet even there, at the heart of an ancient county that knows its history as well as anywhere in France, not one person in a thousand could tell the awful history of the river. Few realise that there were times when it was not so tame, or can point to where the outlines of an ancient fortress can yet be traced, up on the heights above the dam. And almost nobody recalls the lord of that forgotten castle, or could tell you why, until about 150 years ago, Breton peasants crossed themselves at the mere mention of his name.

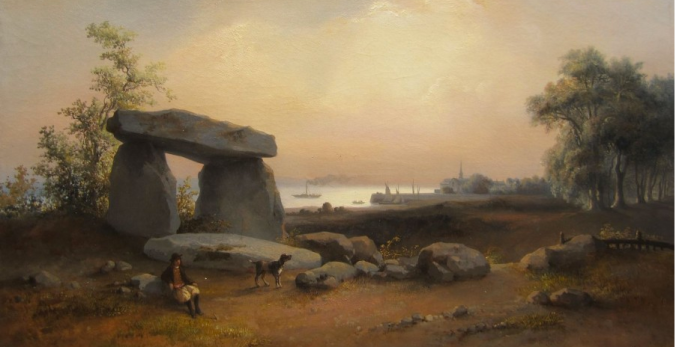

His name was Conomor the Cursed, and he lived in the darkest of the Dark Ages – in the first half of the 6th century, 150 years or more after the fall of Rome, when much of Brittany was still dotted with dolmens and covered by primeval forest, when warlords squabbled with one another other over patrimonies that were generally less than 40 miles across, and the local peoples were as likely to be pagan as they were Christian. We know almost nothing about him, save that he was probably a Briton, very probably a tyrant, and that his deeds were remembered long enough to give rise to a folkloric tradition of great strength – one that endured for almost 1,500 years. But the folk-tales hint at someone quite extraordinary. In local lore, Conomor not only continued to roam the vast forest of Quénécan, south of his castle, as a bisclaveret – a werewolf – and served as a spectral ferryman on another Breton river, making off with Christian souls; he was also the model for Bluebeard, the monstrous villain of Charles Perrault’s famous fairy tales.

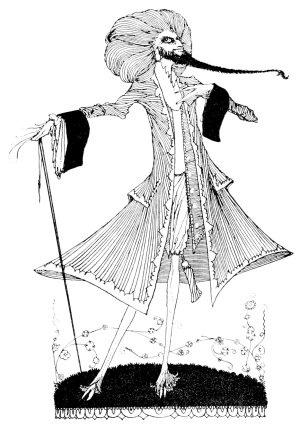

Bluebeard himself, of course, has fallen through the cracks of our collective memory. His tale is seldom told these days; it is far too bloody to sit comfortably alongside the Disneyfied versions of Perrault’s more celebrated stories – his single volume, known familiarly to English-speaking readers as the Tales of Mother Goose, also introduced the world to Sleeping Beauty, Cinderella, Puss in Boots and Little Red Riding Hood. That’s because, while he bowdlerised his other tales, all told originally by adults for adults (Perrault ignored – to give just one example – an older version of Little Red Riding Hood in which the child performs a striptease for the lecherous wolf), the account he span of Bluebeard reads like a treatment for a modern horror movie.

Bluebeard – so this version of the age-old story goes – is a man of immense wealth, and husband to any number of mysteriously vanished wives, but he is rendered hideous by the disfigurement of his strange beard. (It’s worth bearing in mind that, while blue was the colour of the aristocracy at the time that Perrault wrote, beards, with all their associations with unbridled sexuality, were firmly out of fashion at the court of Louis XIV.) He courts two beautiful sisters, and, by showering them with hospitality, persuades the younger of the pair to marry him. Soon after the wedding, though, Bluebeard is called away on business. Summoning his wife to him, he hands her a great bunch of keys, telling her that they give access to every room in their vast mansion, with all the collections of gold and silver plate that they contain. Only one room is forbidden to her – the one behind a locked door at the end of a long corridor, opened with the smallest key of the whole bunch. Entry to that room is taboo, and Bluebeard warns his bride, in graphic terms, of the terrible rage she will stoke in him if she ever dares to enter it: “Open anything you want, go anywhere you wish. But I absolutely forbid you to enter that little room, and if you so much as open it a crack, there will be no limit to my anger.”

Bluebeard departs and, naturally enough, his bride is so consumed with curiosity that she rushes straight to the forbidden room, almost falling downstairs and breaking her neck in her haste. Pausing only for a second to recall the promise that she made to her husband, she thrusts the small key into the lock, turns it, opens the door – and finds herself confronted by a terrible scene. The floor is thick with clotted blood, and the decapitated bodies of Bluebeard’s former wives hang from the walls. Each has had her throat slit, and – in several versions of the tale – much of the blood that they have shed has been collected in an enormous basin that squats monstrously in the centre of the room.

The young wife is so horrified by this sight that she drops the key to the slaughter chamber into the pool of blood lapping at her feet. Hurriedly, she bends to pick it up – only to find that the bloodstains on it cannot be removed. No matter how hard she buffs and scrubs it, the blood that coats the key returns, first on one side, then the other. It is readily apparent to the reader that it must be charmed, and, indeed, as soon as Bluebeard returns from his business trip and calls for his wife, he recognises the significance of the reddened key. Knowing that his bride has ignored his orders (though, as Maria Tatar points out, he surely wanted her to disobey), he tells her that she has sealed her fate, and will be the next victim of the locked room.

Bluebeard’s wife pleads earnestly for mercy, but her husband will not yield, and the one concession she can wring from him is permission to go and dress herself in preparation for her execution. In several versions of the story, she ascends to her bedchamber in order, so she says, to don the gown that she was married in. In fact, though, this is simply a ruse. Her brothers have promised to come and visit her, and she sends her sister to the highest tower to watch for signs of their arrival.

It is here that Perrault ratchets up the suspense. Twice the trembling bride calls up to ‘Sister Anne’ (the one person in the story who is actually named) to ask if her brothers are in sight; twice she receives the answer that “all I see are the flurries of the sun, and the grass turning green.” All this time, Bluebeard is standing at the foot of the stairs, shouting up for her in ever angrier and more urgent tones, while his wife calls down with ever-flimsier excuses. At last she can delay no longer, but at this crucial moment the clouds of dust thrown up by her brother’s galloping horses can be seen at last, and just as Bluebeard drags her to the execution-place, the door bursts open, the brothers appear, and the monster flees, only to be cut down by their swords. In the denouement, Bluebeard’s wife uses his riches to affiance her sister to a man she loves, find herself a second husband, and buy her brothers commissions as officers in the king’s army. There is no further mention of her slaughtered predecessors, nor of the anguish that her discoveries must have caused their families.

Many scholars have searched for Perrault’s sources. It seems to be a fact that the story of Bluebeard appeared nowhere in print before the Frenchman published it in 1697, but the accumulated research of generations of critics and folklorists has shown that, while myriad versions of the tale existed among the oral traditions of most parts of France – and there are equivalents in many other countries, in every one of which the Bluebird-figure is portrayed as the cruellest monster ever to walk the earth – the largest number come from Brittany, and the historic figures most closely associated with the Bluebeard myth are Bretons, too. They are Gilles de Rais, the notorious libertine and boy-murderer who befriended Joan of Arc, and Conomor the Cursed.

The case for associating Gilles with Bluebeard seems weak to me, dependent more on the French nobleman’s general notoriety as a heretic, paedophile and serial murderer than on any real parallels between his history and legend; there are no wives in his story. The case for Conomor is stronger, insofar as elements of Perrault’s tale at least accord with the vigorous traditions of Brittany. Legends that saw print as early as 1514, when Alain Bouchart published his Grandes Chroniques du Bretagne, associate Conomor with wife-killing, and suggest that, because the Breton count had been warned by a soothsayer that he would meet his death at a child’s hand, he was in the habit of disposing of each spouse as soon as she revealed her pregnancy. The association between Conomor and Bluebeard grew from there; he is a “wicked and vicious lord” and “Comorre ar miliguet” (“Conomor the Cursed”) in Albert Le Grand’s work of 1636, and was first linked directly to Bluebeard by Pierre Daru, writing in 1826; Jules Michelet, the great French historian of the nineteenth century, called him an “exterminating beast.”

The Conomor of legend was ruler of the northern Breton coast, with his main seat at Carhaix. It seems that he was also some or all of the Comorre, Conomorus, Kynwawr, Cunmar, Chonomor, Choonbro, Chonobor, Commorus, Chonomorem, Cvnomoriv and Choonober who feature in the chronicles and monuments of the time (the name has been Latinised, rendered from Franconian into French, hastily copied, confused with that of other rulers, or left in its native Old Brythonic, but it always means something along the lines of “Hound of the Sea”). He appears with considerable frequency in a cluster of Breton saints’ lives written some time during the ninth century, supplying the necessary villainy to stories of the holiness of St Paul Aurelian, St Samson and St Gildas. The most elaborate versions of his legend do dwell briefly on the manner in which he came to power – by overthrowing and killing his predecessor, Jonas, and driving Jonas’s son, Judwal, into the arms of the neighbouring Franks – and on his unpleasant character; according to the Breton author Emile Souvestre, “he was a giant, one of the wickedest of men, held in awe by everyone for his cruelty. As a boy, when he went out, his mother used to ring a bell to warn people of his approach. When unsuccessful in the chase he would set his dogs on the peasants to tear them to pieces.” For the most part, however, they revolve around consequences of his marriage to a Breton girl, Tryphine or Tréphine, the beautiful daughter of Waroch (or Guérok), Count of Vannes.

It is in these saints’ lives that we encounter the Conomor who most resembles Bluebeard. He was – Albert Le Grand avers – a tyrant who had already murdered four wives when his eye fell on the beautiful Tryphine. Being known throughout all Brittany for his cruelty and vices, Conomor could not persuade the girl and her father to assent to a marriage. Instead, he resorted to a cunning stratagem. At a time when Brittany had long been wracked by fighting between rival petty rulers, who between them had brought misery to the peninsula, he offered Waroch peace in exchange for Tryphine’s hand.

Arrangements for the marriage were brokered by St Gildas – Gildas the Wise, a noted holy man who had been born in Wales and who had come to Brittany in search of nothing more than a quiet spot in which he could settle down as a hermit. The turbulence of the peninsula soon put an end to that idea, and Gildas instead attached himself to Conomor’s court “in the hope of converting that ravenous wolf into a meek lamb.” Sent to negotiate with the Count of Vannes, the saint eventually persuaded Waroch to accept the marriage proposal – on condition, that is, that Gildas himself guaranteed that Conomor’s bride would be “well treated, and restored to him, healthy and whole, when he should demand her of him.”

For a short time – the same saints’ lives continue – all was well, and Conomor made a concerted effort to be charming to Tryphine. But then something happened to change matters for the worse. There are two traditions here; in one, Conomor is entrapped by another girl at court, who is able to make him fall for her by taking a tumble from her horse in such a way that she inflames his passions with a display of shapely ankle; the count seeks to free himself to pursue her by disposing of Tryphine. In the other, Conomor’s new bride finds herself pregnant, and hence incurs the wrath of a husband who believes their child will grow to kill him.

In Lewis Spence’s version of the legend, a silver ring that Gildas had given her to warn her of approaching evil turned “black as a crow’s wing.” She

descended into the chapel to pray, [but] when she rose to depart, the hour of midnight struck, and suddenly a sound of movement in the silent chapel chilled her to the heart. Shrinking into the recess, she saw four tombs of Conomor’s wives open slowly, and the women all issued forth in their winding sheets.

Faint with terror, Tryphine tried to escape, but the spectres cried, “Take care, poor lost one! Conomor seeks to kill you.”

“Me?” said Tryphine. “What evil have I done?”

“You have told him that you will soon become a mother; and, through the Spirit of Evil, he knows that his child will slay him. He murdered us when we told him what he has just learned of you.”

“What hope then of refuge remains for me?” cried Tryphine.

“Go back to your father,” answered the phantoms.

“But how will I escape Conomor’s guard dog in the court?”

“Give him this poison which killed me,” said the first wife.”

“But how can I descend yon high wall?”

“By means of this cord with which he strangled me,” answered the second wife.

“But who will guide me through the dark?”

“The fire that burnt me,” replied the third wife.

“And how can I make so long as journey?” returned Tryphine.

“Take this stick which broke my skull,” rejoined the fourth spectre.

Armed with the poison, the rope, and the stick,Tryphine set out, silenced the dog, scaled the wall, and miraculously guided on her way through the darkness by a glowing light, proceeded on her road to Vannes.

Unfortunately for the girl, she was making her escape on the only horse available, a haquenée (“an ambling nag”). She did not get very far before an enraged Conomor overtook her, dragged her out of the thicket where she had vainly sought to hide herself, and, ignoring her tearful pleas for mercy, lopped her head from her body with one stroke of his sword.

Waroch was alerted to the outrage by a group of Tryphine’s servants. The grieving count had his daughter’s head and body brought to him at Vannes, and there he confronted Gildas and reminded the holy man of the promise he had made to restore the girl to him “healthy and whole.”

Much affected, Gildas prayed fervently, and then

approached the body, and, taking the head, placed it on the neck; and then, speaking to the defunct, he said to her aloud: “Tryphine, in the name of Almighty God, Father, Son and Holy Ghost, I command thee to rise upon thy feet, and tell me where thou hast been.” The lady rose, and before all the assembled people, she said that the angels had been preparing to place her in Paradise, among the saints, when the words of St Gildas had called her soul back to earth.

There is, of course, a postscript to the legend: having resurrected Tryphine, Gildas travelled along the banks of the Blavet to where Conomor’s fortress, Castel Finans, loomed on a rocky promentory above the river. The count had the castle gates closed as he approached, but the saint merely knelt, picked up a handful of dust, and flung it against the walls – which promptly crumbled just like those of Jericho. In at least some versions of the legend, Conomor himself survived this disaster to retreat to a second stronghold, but there, in solemn conclave, Gildas led the 30 bishops of Brittany in anathematising him, whereupon the tyrant was immediately seized by a “terrible malady,” and his soul born off bobbing on “a stream of blood.” But a potent Breton legend asserted that Conomor’s evil was such that he was denied entry to both Heaven and to Purgatory, and instead remained on earth to haunt the dark, rock-strewn interiors of the ancient forest of Quénécan in the form of a werewolf – one that devoured travellers who passed that way, and could be killed only by the thrust of a knife right through the centre of his forehead.

Approaching all of this as an historian, rather than a story-teller, it is sensible to ask, first, what – if anything – such saints’ tales can tell us about what was really going on in Brittany in the sixth century. It should go without saying that the Lives from which these details have been lifted are notoriously suspect sources. Those that dwell on Conomor were not only composed three centuries after his death, in the ninth century; they were also written as hagiography, in conventional styles, and designed to convey morals and religious messages, not facts. We ought to be deeply suspicious of their contents; certainly it would be dangerous simply to discard their evidently legendary trappings, and hope thereby to recover a residue of solid history. The testimony of the saints’ lives, in short, requires corroboration – and to go back any further, and attempt to detect the relicts of an historical Count Conomor, means travelling well beyond the range of almost every chronicle. It means relying on just a handful of written sources, and some ambitious archaeology.

The chief problem confronting would-be historians of this period is that the Brittany that Conomor knew was a land at the periphery of almost everybody’s interests. Abandoned by the Romans after 380, the peninsula had been swept by successive waves of barbarians and colonisers for well over one hundred years; the Life of St Paul Aurelian mentions it as a “land of four languages,” suggesting that Latin (from Italy), Old Franconian (drawn from Germany’s North Sea coast), Brythonic (from Britain) and also Alan (originating in what is now Iran) were all spoken in these districts at this time. The Breton peninsula also lay beyond the borders of the burgeoning Frankish state, which in Conomor’s day already stretched from Aquitaine in south-eastern France all the way to Thuringia, abutting what is now the Czech Republic. As such, Breton history is mostly ignored in the one almost contemporary source we have, the Historia Francorum (History of the Franks) of Gregory of Tours, completed in 594. And, aside from Gregory, our sources for the period are limited to scraps – this despite the fact that one of the main protagonists of Conomor’s story, Gildas, was himself the author of another notable early work: a sermon, focused on the failings of the kings of Britain, which fails to make any mention whatsoever of Conomor. For now, the thing to remember is that the doings of the petty warlords who established toeholds in sixth century Brittany were noticed only when they interfered with the smooth running of the larger states to the east.

All we really know, in consequence, is that – by around 550 – Brittany consisted of several rival polities, the largest of which was the one we now associate with Conomor: Dumnonia, along the northern coast. Warfare – at least in the form of raids and skirmishes – was more or less endemic in the district, not only between the various Breton counts but also between the Bretons and the Franks. By later standards, though, the causes of conflict were generally petty ones; the chronicles record attacks on Rennes and Nantes that were apparently mounted with the aim of seizing the grape harvest of the Loire valley and escaping back to Brittany with the wine. The Franks retaliated by seizing hostages and taking sureties from their fractious neighbours to the west.

All this is broad-brush stuff, and there’s no avoiding the fact that – as Wendy Davies glumly concludes her survey of the period – “for the most part, we simply do not know what was happening in Brittany” during these years. The fragments that do survive tell us this about the historical Conomor: that he ruled over as much as half of the peninsula; that his base was in the north; that he ruled from some time prior to 540 until around 560; and (at least according to the saints’ lives) that he was eventually defeated in battle somewhere in the Monts d’Arée, in remote Finistére, where he was personally slain by Judwal, the son of Jonas – Jonas being the count whom Conomor, in his turn, had supplanted. None of this is checkable, of course, though it is tempting to read into the last, too-good-to-be-true, account the origins of the tradition that Conomor feared being killed by a child. At any rate, the story of the tyrant’s fall resonated powerfully in Brittany; as late as the second half of the 19th century, a block of slate that lay exposed at a spot called Brank Halleg (Breton for “willow bough”), outside the hamlet of Mengleuz, was pointed to as Conomor’s tomb. “Beneath that block, said the peasants” – Ernest Vizetelly writes – “lay the bones of the tyrant, awaiting the sounds of the judgement trump.”

There is a bigger story here – Judwal seems to have spent his years of exile at the Frankish court, and Gregory of Tours presents his struggle with Conomor as part of a wider conflict that took place in the late 550s between the much more powerful Frankish king Chlothar I (reigned 511-558) and Chlothar’s ambitious son Chramn. Since this civil war is both patchily chronicled and frankly confusing, there is not much to be gained from an attempt to contextualise. It is more interesting, and hopefully more profitable, to turn instead to the ways in which the history of Conomor the Cursed can illuminate the most puzzling and contested aspect of Breton history in this period: the nature of Brittany’s relationship with Britain.

The dispute here is a fundamental one. Nobody doubts that the Britons of this period sailed south to establish themselves in Brittany. Close connections were undoubtedly maintained across what we now know as the English Channel; a glance at the map [above right] shows a couple of examples of the fascinating and widespread duplication of place-names (Dumnonia/Dumnonia; Cornwall/Cornouaille) that exists between south-west England and the Breton peninsula. What is far less certain is whether the leaders who travelled to Brittany from the fourth century onwards left their lands in Britain behind – or whether there were rulers active and powerful enough to reign on both sides of the water.

In attempting to tackle this problem, we need to point, first, to the reasons for British emigration in this period. Abandoned by the Rome, and then confronted by Anglo-Saxon migration in the years 450-550, the Celtic inhabitants of Britain fell back to the the west, where the land was higher, rougher and more inaccessible, and where much of the soil was so poor that the invaders had little motive to press for further conquests. In consequence, British kingdoms continued to exist to the north (in Strathclyde, with its capital at Dumbarton – which means “the fortress of the Britons” – c.450-c.1030); in Wales; and to the south, in Devon and Cornwall, where the state known as Dumnonia was certainly in existence well before 550 and survived as late as about 839.

But if a key factor in the existence of these states was geography, the same features that allowed the Celts to retain their independence also caused them serious difficulties. There was little decent land available in the highlands, and Celtic law prescribed the division of each father’s possessions among all his sons. In such circumstances, the progressive dividing up of patrimonies inevitably produced poverty and encouraged the Britons of both Cornwall and South Wales to look hungrily over the Channel for land. It is generally supposed that this emigration began no later than 350, and we know there was enough of it for a “bishop of the Britons” to have travelled from Brittany to attend the Council of Tours, which was held in 461, and for the Brythonic and Breton languages to remain indistinguishable as late as the 10th century. Small states controlled by rulers with British names existed in the Breton peninsula after 500, and in the course of the sixth century enough Britons emigrated to France, with sufficient success, for a clearly independent collection of Breton polities, with their own language and distinct identity, to have emerged a century later.

All this certainly suggests something much more interesting than the emigration of some scattered families, but it is not enough to prove that the Britons who sailed south were politically significant or that they retained lands and power in their homeland. There are, indeed, reasons to suppose that this was not the case; educated guesswork suggests that British control in Brittany was far stronger in the countryside than in its towns, where Roman and Frankish influences still predominated in this period. That, and the fact that no identifiable British “high king” emerged south of the Channel in the sixth century, argue against the existence of a ruler powerful enough to control significant territory in both Cornwall and Brittany. Even Conomor the Cursed, remember, was only a count, and ruled no more than the northern shores of the peninsula.

This reasoning cleaves to the line of least resistance, and eminent authorities on the period, among them Wendy Davies, follow it. Yet there is other evidence. Dumnonia was easily the biggest of the British kingdoms that survived the westward push of the Saxons – at its height it was something like 125 miles (200km) from end to end, making it among the largest states, by area, in all of Britain at this time. That suggests rulers of some prominence, and a degree of organisation that might have been sufficient to permit projections of their power. Conomor’s name – “Hound of the Sea” – and the powerful traditions of the Breton saints’ lives, which present him as an “unjust and unprincipled stranger” – an outsider, in other words – both suggest a possible origin in Dumnonia as well.

The most interesting fragment of evidence, though, comes from the Life of St Paul Aurelian – a much later source, remember, completed in 884, and thus one that must be treated with great caution. This mentions a “King Marcus whom by another name they call Quonomorius” – and this extract has been taken as a reference to the semi-legendary King Mark of Cornwall who figures prominently in medieval Arthurian romance and plays an especially important part in the story of Tristan and Yseult (that is, Tristan and Isolde ). In this romance, Mark is a king of Cornwall – Dumnonia – and Tristan is his nephew, sent to Ireland to bring back Mark’s beautiful young bride, who instead, inevitably, falls in love with the girl himself.

Now, it is true that the King Mark of Arthurian romance makes his first appearance in literature at least 500 years after the historical King Mark lived and ruled – if indeed he ever lived at all. And it’s also true that no source dating to before St Paul Aurelian makes mention of a Mark of Cornwall. So we are sailing here in very dangerous waters. But a connection can still perhaps be made, for a late Welsh list of the Dumnonian kings – held at Jesus College, Oxford (MS.20), though probably copied no earlier than the late 14th century – includes a “Kynwawr” who would have reigned shortly before 550. From an etymological perspective, Kynwawr can be identified with both Cynfawr (a name known to have existed in 6th century Wales), and the Latin Conomorus. Thus, if credence can be placed in the king list, a king called something very like Conomor ruled in Dumnonia at pretty much the same time as a Count Conomor ruled in Brittany; and if credence can be placed in the Life of St Paul Aurelian, this Conomor might also be the same person as the King Mark of Cornwall whose name remains indelibly associated with Arthurian romance. And if both these things are true, then the Conomor who features as the Bluebeard of Breton legend might indeed have been a British king of considerable power and resources, whose domains included lands on both sides of the Channel.

There is at best only an outside chance that this extensive chain of surmise stands much scrutiny, and the association of King Mark with Kynwawr of Dumnonia has proved to be, by itself, enough of a lure to have generated some highly dubious scholarship, which has come to muddy the waters of even quite respectable historical journals – as the afterword to this essay seeks to demonstrate. Things can only get more tangled and less rigorous if we attempt to add Breton werewolves and wife-killers to the mix. The idea remains, though, an enticing one. And a Conomor who had his roots in Wales or Cornwall remains the best candidate by far for the cursed count who haunted medieval Brittany, and caused even the peasants of the 19th century to mutter prayers whenever they heard his name.

Anyone searching for the historical Conomor online will soon encounter references to an ancient monument in Cornwall which not only seems to refer to him, and provide additional evidence for the existence of a powerful British ruler who controlled territories on both sides of the Channel during the sixth century, but which has also been linked directly to the tale of Tristan and Yseult. It has been claimed that this “Tristan Stone” is proof that these two legendary characters were real historical personages, and that Tristan was the son of a King Mark, who was also known as Conomor, and who ruled from an important hill-fort, Castle Dore, which can still be seen a mile or two to the north of the spot where the monument now stands.

Today the “Tristan Stone” is to be found alongside the B3415, just outside the little port of Fowey, on Cornwall’s south-east coast – although the evidence suggests that it was originally erected some way to the north. The stone bears an inscription, now almost entirely worn away, which can be dated by its form and lettering to around the sixth century, and which (at least in the internet consensus) originally read Drvstanvs hic iacit filivs Cvnomoriv cvm domina Clvsilla. This can be – and has been – rendered, with the help of a considerable degree of favourable “interpretation,” as “Here lies Tristan, son of Conomor, with his lady Yseult.”

We’ll return to this interpretation in a moment. But let’s look first at what we know about the stone, its location and its history. What follows, I should note, is drawn from the major academic studies of such stones – those of Macalister and Okasha. I’ll deal with the rival, more ambitious claims of the archaeologist Raleigh Radford and the Arthurian scholar André de Mandach later.

The first thing to say is that, while the stone is estimated to be roughly 1,500 years old, records of its existence date back only as far as the sixteenth century writings of the Cambridge scholar John Leland, librarian and antiquarian to Henry VIII. Leland is of interest to us here because he travelled throughout England and Wales during the years c.1538-43 in order to compile an Itinerary of places, monuments and artefacts; he was in Cornwall in 1542, where he set down the earliest known description of what appears to be the “Tristan Stone.” His work, which was never published in his lifetime, exists today as an original manuscript in the Bodleian Library, Oxford. It was first published, in nine volumes edited by Thomas Hearne, in 1744-45 [vol.III p.26]; between 1907 and 1910, Lucy Toulmin Smith produced a scholarly edition of the work, and the passage that concerns us features here in the first volume (part III p.207): “Casteldour is longgid to [belongs to] the Erle of Saresbyri [Earl of Salisbury]. A mile of [off] is a broken Crosse inscribed: Conomor & filius cum Domina Clusilla.”

The second thing to point out is that the stone has moved – and, apparently, fragmented – in the time since Leland implied he saw it. If it was one mile from Castle Dore in 1540, then it was a full two and a half from Fowey, and Okasha summarises its subsequent movements as follows: it was relocated, probably before 1602, to a spot about a mile and a half away, on the roadside one mile from Fowey; by 1742 it had been dumped in a ditch along the Castledore road near Newton, where it was soon “half-buried” in accumulated muck; it was set upright once more about 1803, at the same spot; it was moved again, shortly before 1894, to “the centre of the highway outside Menabilly Lodge gates”; and in 1971 it was shifted yet again, slightly to the south, and re-erected at the place where it can now be found.

This is a history that combines periods of rough care with longer stretches of utter lack of care, and it is not very surprising that the inscription on the stone has become far less readable than it was when Leland apparently saw it. The wording itself is now in two lines, reading downwards and facing left. (Leland’s interpretation may imply there were once three.) It is in Latin, in capital script, and – thanks to its murky, deteriorated condition – it has been read rather differently by the various people who have seen it. The versions that have been published along the way include those of William Camden, in his Britannia of 1586; of the Welsh antiquary Edward Lhwyd (a friend of Isaac Newton’s who was Keeper of the Ashmolean Museum at the University of Oxford and a noted student of the Cornish language), in a private letter of 1700; of the Cornishman William Borlase, in his Antiquities of Cornwall, 1754; and of Daniel and Samuel Lysons, in the third volume of their Magna Britannia, 1814.

Listing these various interpretations in order of date, we have [with a slash, “/”, denoting a break between the lines, “-” an illegible character, ” and “{x}” a special character (in the case of the “Tristan Stone,” these are inverted letters – the letter ‘w’ being apparently represented, though it did not actually come into use until about 1100). The single exception here is the argument of John Rhys, Raleigh Radford and André de Mandach that the first letters, “Cl” should actually be read as a “D” carved in unical script)]:

CONOMOR & FILIUS CUM DOMINA CLUSILLA [Leland, 1542]

CIRVIVS HIC IACET / CVNOWORIS FILIVS [Camden, 1586]

CIRUSIUS HIC JACIT / CUNOWORI FILIUS [Lhwyd, 1700]

CIRVSIVS HIC IACIT / CVNOWORI FILIVS [Borlase, 1754]

CIRUSIUS HIC JACET / CUNOWORI FILIUS [Lysons, 1814]

DRUSTAGNI HIC IACIT CVNOWORI FILIVS [Rhys, 1875]

CIRVSINIVSHICIACIT / CVNO{M}ORIFILIVS [Macalister, 1945]

[CIRV–V–NCIACIT] / CV[N]O[{M}]ORFILVS [Okasha, 1985]

{D}RVSTA/NVSHICIACIT / CVNO{M}ORIFILIVS [Thomas, 1994]

I make no claim to any expertise in the interpretation of ancient stone inscriptions, but a couple of things seem readily apparent here. The first is that increasing wear on the inscription (and very likely also increasing scrupulousness on the part of its interpreters) caused some individual letters on the monument to be become – or be acknowledged as – illegible between the eighteenth and the twentieth centuries. The second is that there is a very dramatic difference between the inscription as given by Leland in 1542, and the inscription reported by every other witness, beginning with Camden four decades or so later.

These distinctions become important when we turn to the work of André de Mandach, a Swiss scholar of Arthurian legend who is the most important reinterpreter of the inscription. Although it seems to have been John Rhys, the inaugural Professor of Celtic at Oxford, who first proposed (in 1875) that the stone was erected in memory of a “Drustagni,” and it was certainly Raleigh Radford (in the 1930s) who argued that it commemorates the Tristan of medieval romance, it was de Mandach who did most to tie all this together. His work places great stress on the primacy of Leland’s version of the inscription, and uses it to tie it to the Tristan legend by arguing that Clvsilla = Clu-silla = “blonde flower” [ancient Irish] = Isolde. De Mandach goes on to propose that Leland encountered the stone when it was not only significantly more legible, but also significantly more complete, than it was found by any modern visitor. He points out, by comparing sketches, that it seems to have been then about 25 inches (63cm) wide, whereas the monument we see today is only 13 inches (33cm) across. There is certainly something in this argument; we have a sketch [below right], published by Borlase midway through the eighteenth century, which shows the monument – known in those days merely as the Long-Stone – in something more nearly approaching its original shape. The reason for its deterioration, by the way, is probably that the original stone was adapted to be surmounted by some sort of cross; this became detached at some point before Leland’s visit to it, exposing a mortise in the top of the remnant. This hole allowed water to collect and begin a slow process of degradation via successive freezings and thawings.

Cutting what is threatening to become a lengthy story as short as possible, de Mandach’s argument is that a third line, originally part of the inscription, was lost as a result of this shrinkage; he proposes that Leland reported the second and third lines of an original three-line inscription, while every person who came after him transcribed only the first and second lines. This dichotomy, he argues, can be resolved by supposing that the third line was lost to the process of “shrinkage” after Leland saw it.

Yet there are good reasons for supposing that this cannot be so, and in fact de Mandach’s own evidence does not support his argument. He prints Borlase’s engraving, which depicts the monument at its full width, and clearly shows only a blank space where Leland’s third line ought to be; if we assume the old antiquary’s reading was correct, then his CVM DOMINA CLVSILLA must therefore have been lost to erosion, not to the gradual degradation of the stone itself. But – given that Borlase wrote well before the stone spent decades lying in a ditch, while Okasha points out that the second line of text is better preserved than the first – there seems no obvious reason why a third line should disappear completely, while the one above it remained entirely legible.

In much the same way, it is also notable that Camden’s version of the inscription reads entirely differently to Leland’s, even though it dates to less than half a century after it. Even today’s much more scarred and worn-down monument is not deteriorating at the sort of rate that would be required for an entire line of text to go missing between 1542 and 1586, and the only reasonable alternative is that one of the two sixteenth century transcriptions that have come down to us has to be in error. Which one? Camden’s closely resembles those of later travellers and antiquaries; Leland’s does not. It seems possible to conclude that (for reasons that are now entirely lost to us) Leland comprehensively mistook, misnoted or misreported the inscription – or, more probably, given his abilities as a scholar, merely took it down from some local who had mistaken or misreported it. And there’s another, even better, reason for doubting the interpretation championed by de Mandach, Radford and Lloyd: the results of new scans of the stone, by Adam Spring and Caradoc Peters, using 3D imaging techniques, have very recently confirmed that the “C” and the “l” at the head of the inscription are separate. That means that the name of the dedicatee really is “Clusilus,” not “Drustanus.”

We’re left with a monument that seems to date to about our period, which must have been produced by a family possessed of considerable resources, which was set up near an important castle, and which commemorates the son of a “Conomor” – albeit one who was almost certainly not named “Tristan”. It’s not implausible that the Conomor in question was the same man as the Breton Bluebeard, nor utterly impossible that he was the King Marcus/Quonomorius of the Life of St Paul Aurelian. But, equally, there is no proof at all that he was either of these things. For all we know, “Conomor” was a common name at this time, given to many members of many noble families. The Long-Stone thus adds little to our quest for an historical Conomor the Cursed, raising more questions than it answers.

What all this shows, I would contend, is the great danger of wanting something to be so. Both Raleigh Radford and André de Mandach seem to have been guilty of this sin. Radford wanted to find evidence that a significant British civilisation had survived the departure of the Romans; excavating at Castle Dore, a few miles north of where the “Tristan Stone” stands, he uncovered some post-holes and a couple of fragments of old pottery, and dated them to the years after Rome’s withdrawl – “proving” (and not just in his own mind, for his findings were not challenged for nearly 40 years) that Castle Dore had been the palace of King Mark of Cornwall, and the likely capital of a substantial Dumnonian government. Both Radford and de Mandach also badly wanted to demonstrate that the Arthurian legends had historical roots in the same time and place. This need led them into convoluted arguments, and most dangerously it prompted them to reinterpret evidence in ways that suited their own carefully prepared cases. It was for this reason that both men were willing to interpret the hazily-carved, badly worn first letters, CI, on the Fowey monument as a single letter “D,” improbably inscribed in quite a different script to that which followed – a peculiarity that would make the stone utterly unique among all the early Christian memorial stones that have survived in England, Wales and Ireland.. It was this bit of palaeographical contortionism that allowed them to read the inscription not as a reference to “Cirusius” but as “Drustanus” – Tristan – and turn the Long-Stone into the “Tristan Stone” that pops up on the internet today.

It is romantic. But it is scarcely history.

Albert le Grand. Les Vies des Saints de la Bretagne-Amorique. Brest: P. Anner et Fils, 1837; Bernard S. Bachrach. A History of the Alans in the West. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1973; Brigitte Cazelles and Brett Wells. “Arthur as Barbe-Bleu: the Martyrdom of Saint Tryphine.” In Sahar Amer and Noah D. Gunn (eds), Rereading Allegory: Essays in Memory of Daniel Poirion. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999; Celtic Inscribed Stones Project database, compiled by the Department of History and Institute of Archaeology, University College London, accessed 28 December 2015; TM Charles-Edwards. Wales and the Britons, 350-1064. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013; Wendy Davies. “The Celtic Kingdoms.” In Paul Fouracre (ed). The New Cambridge Medieval History I, c.500-c.700. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005; Sidney Hartland. “The forbidden chamber.” The Folklore Journal 3 (1885); Casie Hermansson. Bluebeard: A Reader’s Guide to the English Tradition. Jackson [MS]: University of Mississippi Press, 2009; Historic England. “The Tristan Stone, early Christian memorial stone and wayside cross, 75m north of Polscoe,” 8 December 1997. Accessed 27 December 2015; “Mr Canon Kendall to Mr Moyle,” 1717/18, in The Gentleman’s Magazine May 1838; Gy Kroó. “Duke Bluebeard’s Castle.” In Studia Musicologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 1 (1961); Marianne Micros. “Robber bridegrooms and devoured brides.” In Mary Ellen Lamb and Karen Bamford (eds), Oral Traditions and Gender in Early Modern Literary Texts. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2008; R.A.S. Macalister. Corpus Inscriptionum Insularum Celticarum vol.1. Blackrock, Eire: Four Courts Press, nd (c.1996); André de Mandach. “The shrinking tombstone of Tristan and Isolt.” Journal of Medieval History 4 (1978); Elsie Masson. Folk Tales of Brittany. Philadelphia: Macrae Smith, 1929; Elisabeth Okasha. Corpus of Early Christian Inscribed Stones of South-West Britain. Leicester: Leicester University Press, 1993; Susan M. Pearce. “The traditions of the royal king-list of Dumnonia.” Transactions of the Honourable Society of Cymmrodorion 1971 Part 1 (1972). Susan M. Pearce. The Kingdom of Dumnonia: Studies in History and Tradition in South Western Britain, AD 350-1150. Padstow: Lodenek Press, 1978; Charles Perrault. “Blue Beard.” From Tales of Mother Goose. Accessed 27 June 2015; Philip Rahtz. “Castle Dore – a reappraisal of the post-Roman structures.” Cornish Archaeology 10 (1971); John Rhys. “Some of our inscribed stones.” Archaeologia Cambrensis. 4S. VI (1875); Christopher A. Snyder. The Britons. Malden [MA]: John Wiley, 2003; Lewis Spence. Legends and Romances of Brittany. London: George Harrap, 1917; Adam P. Spring and Caradoc Peters. “Developing a low cost 3D imaging solution for inscribed stone surface analysis.” Journal of Archaeological Sciences 52 (2014); Clare Stancliffe. “Christianity among the Britons, Dalriadan Irish and Picts.” In Paul Fouracre (ed). The New Cambridge Medieval History I, c.500-c.700. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005; Maria Tatar. Secrets Beyond the Door: the Story of Bluebeard. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2006; Charles Thomas. And Shall These Mute Stones Speak? Post-Roman Inscriptions in Western Britain. Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 1994; Lucy Toulmin Smith [ed.] The Itinerary of John Leland in or about the Years 1535-1543, parts I to III. London: George Bell and Sons, 1907; Ernest Alfred Vizetelly. Bluebeard: An Account of Comorre the Cursed and Gilles de Rais, with Summaries of Various Tales and Traditions. London: Chatto & Windus, 1902; Marina Warner. From the Beast to the Blonde: On Fairy Tales and Their Tellers. New York: Vintage, 1995; Micheline Walker. “Bluebeard: motifs & suspense.” Micheline’s blog, accessed 9 June 2015.

Search keys: Cunmar the Cursed, Cunmar the Accursed, Conomor the Accursed, Comorre the Accursed.