(Author’s Note: This year marks the 145th anniversary of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. For the past three weeks, I have been writing a series of posts about Lincoln’s death, as well as the mournful journey of his Funeral Train as it brought his body from Washington, D.C. back home to Springfield, Illinois. I began this series for two reasons. First, to inform others who might wish to learn more about one of the darkest periods in our nation’s history. Second, and more importantly, to offer my own contribution to remembering Mr. Lincoln. To those of you who have read all or part of this series, I offer my thanks and gratitude. Hopefully you’ve taken from this series an even deeper respect for what Abraham Lincoln meant, and continues to mean, to our nation.)

At daybreak in Springfield, Illinois on May 4, 1865, thirty-six guns from Battery K of the Missouri Light Artillery were fired in a national salute to Abraham Lincoln. The guns, one for each state in the Union at the time (including the Confederate states), marked the beginning of the last of the thirteen funerals for the fallen leader. A single gun was fired every thirty minutes after that until nightfall, when another thirty-six gun salute was fired.

The Illinois State Capitol had remained open all night so that as many mourners as possible could walk past the remains. Below is a photo of the coffin laying-in-state in the Capitol, with the lid not yet removed. It was placed at an angle so viewers would have a better angle at which to see the remains.

Accounts I’ve read vary, but the Capitol doors were closed at either 10:00 that morning, or at 1:00 p.m. Undertakers then made the final “cleaning” of the burial suit and sergeants from the Union army carried the casket to the waiting hearse. The hearse, which is shown at the beginning of this post, was as magnificent as those in the other funeral cities. It had been lent to the town of Springfield by the mayor of St. Louis, Mo. because Springfield felt it didn’t possess a hearse grand enough for Mr. Lincoln. The hearse was built in Philadelphia, and cost $1,000 which was a huge sum of money in those days.

On the Capitol steps that day a 250-voice chorus was waiting to burst into a hymn as the president’s remains were placed into the lavish hearse. As the choir sang, a 21-gun salute was fired. Then the last funeral procession began to slowly pull away from the Capitol, on its way to Oak Ridge Cemetery and the waiting receiving tomb.

Leading the procession that day in Springfield was Major General Joseph Hooker, who had been in charge of the military during the funeral journey from Cleveland onward. Ironically, it had been nearly two years to the day since Hooker led Union forces in a disastrous defeat at the Battle Of Chancellorsville (Virginia). Lincoln had removed Hooker from command after that defeat, replacing him just prior to the Battle of Gettysburg. Hooker had been selected by Secretary of War Stanton for the duties of the funeral command, which he performed with great ability and honor.

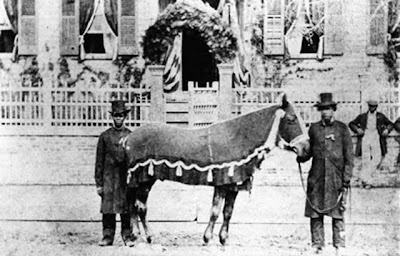

The procession made its way from the Capitol past the Lincoln home and Governor’s mansion, and finally to the road which led to the cemetery, then in the countryside outside Springfield. Behind Hooker marched one thousand soldiers. Then came the hearse, pulled by six huge matched black horses.

Behind the hearse was Lincoln’s horse, “Old Bob”, dressed smartly in mourning with a black blanket covering him. The horse had been used by Lincoln as he rode the law circuit in that part of Illinois, and had served Lincoln for more than ten years through the Illinois countryside. See the below image to see how “Old Bob” looked that day.

Also riding in the procession was the president’s oldest son, Robert, accompanied by a cousin. As was the case with the previous eleven funerals, Mary Todd Lincoln did not attend any of the services. Indeed, she still remained in The White House, too emotionally distraught to leave her bed, let alone make the long journey to Springfield. It would be three more weeks until she could summon the strength to leave for her new (and temporary) home in Chicago, bringing along her younger son, Tad.

The procession at last entered Oak Ridge Cemetery and approached the public receiving vault carved into a hillside. It was meant to be a temporary “final” resting place for Lincoln (and Willie) until Mary Lincoln could return to Springfield to pick a more suitable location in the cemetery for her husband and son. That the “burial” was happening in this particular cemetery at all was somewhat of a fluke.

Immediately after Lincoln’s death, a battle of wills erupted between the president’s widow and the city leaders in Springfield. They had passed a “resolution” claiming Lincoln’s remains, stating that the president deserved to be buried there. Mrs. Lincoln, though, had many enemies in Springfield (as she did in Washington) and was not, at first, willing to have her husband laid to rest in the town which harbored unhappy memories for her. Her original first choice was Chicago, followed by her second choice of the crypt which had been originally built for George Washington in the U.S. Capitol.

Then she remembered that her husband had once told her that he wanted to be buried in a simple, quiet place in the country and decided that Oak Ridge Cemetery in Springfield would fulfill his wish. That wasn’t good enough for the Springfield city fathers, who immediately moved to erect Lincoln’s Tomb in the center of town. When Mrs. Lincoln heard that construction on such a tomb was underway, indeed nearly complete, she immediately fired off a telegram threatening to have her husband buried in Chicago. Finally, they relented, and Oak Ridge Cemetery was used per her wishes.

The temporary vault, seen in the print below, was in a lovely location. Surrounded by trees and with a babbling brook in front as it looked over the valley, the setting satisfied Lincoln’s wish for a “quiet place.”

Mourners lined the hillside above the vault as Lincoln’s casket was removed from the hearse and put inside. Earlier, the casket of his dear son Willie, who had died of typhoid in 1862, had been placed in the same vault. Robert Lincoln and some of the president’s closest friends and advisers flanked the doors during the placement.