I have just finished reading Joshua Rubenstein‘s The Last Days of Stalin, a book I can thoroughly recommend to all who are interested in post-war European history. By and large the theme is not one for this blog but, as one would expect, Sir Winston Churchill appears in it and plays a slight equivocal role.

Chapter 6 is entitled A Chance for Peace? and deals with the opportunity the West, led by President Eisenhower, might have taken to create a more lasting peace or generally come to better terms with the post-Stalin leadership. Professor Rubenstein is inclined to blame Eisenhower and John Foster Dulles, feeling more on the side of such people as the President’s aide, Emmet Hughes who felt frustrated by the “obvious” opportunity created by Stalin’s death, the new leadership’s desire to introduce reforms (to save their own skins rather than because they had any liberal ideas) and to ease up relations with the West.

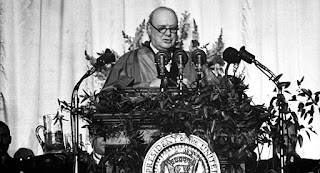

In actual fact, that window of opportunity lasted exactly two months from April 16, 1953 when Eisenhower delivered his Chance For Peace speech to the American Society of Newspaper Editors to June 17 when the two-day East Berlin uprising broke out to spread to other parts of East Germany and to be put down fairly brutally by the Soviet army and the East German police. After that, any idea of German reunification on any condition could be shelved. Within less than ten days Beria was arrested and the Soviet leadership appeared to sink into another internecine warfare.

Even the two months in question were not exactly propitious. There were riots in Plovdiv, Khaskovo and Pilsen, news of discontent in the other East European colonies and uprisings in the political camps of the Gulag. The amnesty brought in immediately after Stalin’s death affected only criminals with the exception of the Doctors’ Plot whose “members” were released and all accusations were quashed. The politicals started demanding that their cases should be reviewed as well and in a number of camps there were genuine uprisings, usually led by Ukrainians, Balts and Poles. At first the authorities were prepared to negotiate but as they were not prepared to offer anything except slightly better working conditions there were no agreements and the uprisings were put down with great ferocity. Officially this was unknown in the West but I find it difficult to believe that some rumous had not crept out to the various security services.

Nevertheless, the book conveys a feeling of frustration and lost opportunity after Eisenhower’s speech without making it very clear what concrete suggestions he should have made, except for one: a summit meeting with, possibly, Georgy Malenkov who appeared to be the leader, though only temporarily.

Eisenhower made it clear that the Soviet union should come up with some concrete proposals first but, above all, he was not a great supporter of summits, believing with some justification that during the war time ones the West had given away too much to Stalin and refusing to recognize, despite his desire to lessen the tension, that the new leadership might be more accommodating.

This is where Churchill hove into view, advocating summits, discussing with the Soviet ambassador to London, Yakov Malik, the possibility of a secret meeting with Malenkov, and speaking forcefully on the need to balance the needs of European countries with “Russia’s” (i.e. the USSR’s) desire for security. In the process he managed to make the Kremlin suspicious, antagonized Chancellor Adenauer and some other West European leaders and seriously annoyed the Americans. He did get a good press from the British newspapers, though.

On May 11, 1953, during the first big foreign affairs debate after Stalin’s death Churchill made a speech [scroll up] in which he tried to reconcile several ideas.

Russia has a right to feel assured that as far as human arrangements can run the terrible events of the Hitler invasion will never be repeated, and that Poland will remain a friendly Power and a buffer, though not, I trust, a puppet State.

I venture to read to the House again some words which I wrote exactly eight years ago, 29th April, 1945, in a telegram I sent to Mr. Stalin: ” There is not much comfort”

I said, “in looking into a future where you and the countries you dominate, plus the Communist Parties in many other States, are all drawn up on one side, and those who rally to the English speaking nations and their associates or Dominions are on the other. It is quite obvious that their quarrel would tear the world to pieces, and that all of us leading men on either side who had anything to do with that would be shamed before history. Even embarking on a long period of suspicions, of abuse and counter-abuse, and of opposing policies would be a disaster hampering the great developments of world prosperity for the masses which are attainable only by our trinity. I hope there is no word or phrase in this outpouring of my heart to you which unwittingly gives offence. If so, let me know. But do not, I beg you, my friend Stalin, underrate the divergencies which are opening about matters which you may think are small to us but which are symbolic of the way the English-speaking democracies look at life.” I feel exactly the same about it today.

I must make it plain that, in spite of all the uncertainties and confusion in which world affairs are plunged, I believe that a conference on the highest level should take place between the leading Powers without long delay. This conference should not be overhung by a ponderous or rigid agenda, or led into mazes and jungles of technical details, zealously contested by hoards of experts and officials drawn up in vast, cumbrous array. The conference should be confined to the smallest number of Powers and persons possible. It should meet with a measure of informality and a still greater measure of privacy and seclusion. It might well be that no hard-faced agreements would be reached, but there might be a general feeling among those gathered together that they might do something better than tear the human race, including themselves, into bits.

The first paragraph would indicate a wilful misreading of what was going on in Eastern Europe (not a puppet state, forsooth!) and what had been going on in Poland in 1939. The rest of it mostly wishful thinking, as was a suggestion earlier in the speech that if Germany was reunited Britain could guarantee peace on the Continent – not a particularly rational suggestion in 1953.

Chancellor Adenauer showed himself to be unhappy with what he saw as an attempt to sacrifice West Germany, a democracy, in order to have some kind of an agreement with the Soviet Union. The Kremlin leadership distrusted Churchill, thinking of him, rather ironically, as the man who wanted to strangle Bolshevism at birth rather than the man who was Stalin’s ally and, some would say, dupe. Molotov, the Foreign Minister, absolutely rejected the idea of a “secret” meeting between Churchill and Malenkov. Furthermore, as Pofessor Rubenstein notes, the Kremlin had a shrews understanding of Churchill’s and Britain’s real standing in the world despite the marks of respect paid to him.

The White House and the State Department paid their respects but pointed out that it was not clear who would represent the USSR and, in any case, the low-level talks about Korea were still getting nowhere. What would a summit achieve?

In Congress, Senate Majority Leader William F. Knowland compared Churchill’s speech to Neville Chamberlain’s appeasement of Hitler at Munich in 1938, a shocking objection given Churchill’s ringing opposition ot Chamberlain’s negotiations with the Nazis.

Shocking maybe but it does raise an interesting question: just what was it about Stalin that made Churchill, the great anti-appeaser into a full-blooded appeaser? He returned from Yalta with assurances for all who doubted in the Cabinet and in Parliament that if there was one man to be trusted on the international scene it was “Premier Stalin”. He preferred to ignore the problem of people being handed over to the Communists, both Soviet and Yugoslav. And judging by the comment he made about Poland in 1953 he did not quite understand the situation in Eastern Europe despite the Fulton speech, which brilliantly defined the situation.

To be fair, there was more sense to Churchill’s 1953 desire to come to terms with the post-Stalin Soviet leadership, even though his assumption that Malenkov will go on being the undisputed boss turned out to be wrong – the heirs of Stalin did exhibit various signs of wanting to negotiate over Korea as well as, possibly, Austria and Germany. They even started allowing the Russian wives of Western diplomats and military officials out of the Gulag and out of the country. But a summit or secret meetings? Could they really achieve anything?

To a great extent one can understand that this was Churchill’s attempt to restore the war-time situation when he did rush around the world, having secret meetings with Stalin, among others and the big three had several summits. Churchill was missing his and Britain’s position at the top and was reluctant to acknowledge the reality of the situation. Sadly, others, the White House and Kremlin for instance, did acknowledge it.

Nevertheless, it is fair to say that his comments about the need to acknowledge Russia’s fears and longings for security were not that different from Germany’s supposed needs in the thirties, needs that he had quite rightly dismissed at the time.

Nothing came of Churchill’s suggestions. Molotov refused to agree to any meeting between Malenkov and Churchill, as did Eisenhower. The window of opportunity closed on June 17 with the uprising in East Berlin and at the end of June Churchill had a stroke, which was hidden from all though it put him out of action completely and much of his business was transacted in his name by his son in law, Christopher Soames and his secretary, Sir John Rupert “Jock” Colville. A “secret disability crisis” is one way of describing those events; I have also heard references to a coup, a very British coup. The idea of the summit, never very strong, was abandoned.